Is it Simply a Notice? Data Transfers Under Scrutiny

-

by

tlcmf

Introduction

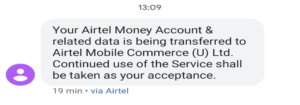

On 15 June 2021, Airtel Uganda Limited (“Airtel”), a telecommunications service provider in Uganda, sent out a message to its customers. It read, “Your Airtel Money Account & related data is being transferred to Airtel Mobile Commerce (U) Ltd. Continued use of the service shall be taken as your acceptance.”

On the face of it, the communication may be regarded as a courteous notice to the Airtel customers, however, when one closely scrutinizes the claims and underlying presuppositions of the communication, it is legally problematic. In this article, we shall first discuss the legality of such communications. Secondly, the article will examine whether the transfer of data with related parties satisfies the requirements under Uganda’s Data Protection and Privacy Act, 2019. Further, the article considers whether obligations from other laws waive the requirements for consent under data protection law in Uganda. Broadly, this article highlights the important aspects of informed consent and specifically whether consent is the best model for protection of privacy rights especially in this digitalized age where data is aggregated by several companies and their intermediaries.

Background and Context

Airtel is licensed as a telecommunications service provider in Uganda and was simultaneously providing mobile money services. The provision of mobile money services was not specifically regulated under Ugandan law, until recently when the National Payment Systems Act, 2020 and the relevant Implementing Regulations of 2021 were enacted. Mobile money services now fall under the regulatory ambit of the National Payment Systems Act as a “payment service” licensed by the Central Bank of Uganda. As a result of National Payment Systems Act, there are now different regulators for telecommunication services and payment systems service providers. As such, it became important to separate the two business models.

Airtel Mobile Commerce (U) Ltd (“Airtel Mobile Commerce”), a “related” company to Airtel on the 21st day of May 2021 was granted a license to operate as a “Payment System Operators”, “Payment Service Provider” and an “Issuer of Payment Instruments”.

Data to Transfer to a “related company”

“Your Airtel Money Account & related data is being transferred to Airtel Mobile Commerce (U) Ltd. Continued use of the service shall be taken as your acceptance.” From the reading of this statement, it can be inferred that the data of Airtel mobile money service customers “is being” or “was” transferred to the Airtel Mobile Commerce on (from) the date the communication was sent.

Was this merely a notice? Or, would the reading of the message coupled with the lack of a subsequent objection amount to acceptance or consent? Aren’t there existing specific legal requirements for the processing and transfer of data?

Airtel Uganda Limited Response

Following a social media complaint challenging the legality of the communication, Airtel through their official Twitter account (@Airtel_Ug) responded as follows, “… this is a notice to our customers that we have separated and transferred the Airtel Money Business to our sister company, Airtel Mobile Commerce Uganda. It’s simply a notice.”

In a series of other tweets, Airtel added that the transfer has no effect on Airtel Money activities and stated that “Your information has not been given out to any third – party company.” But what is a third-party company? Did the Airtel mobile money customers know about the existence of Airtel Mobile Commerce? Airtel Mobile Commerce was not privy to the agreement for the collection of data between Airtel and its customers. As such it may be deemed as a third-party under Ugandan data protection law. Should this third-party arrangement have been legitimized by a consent or simply a notice?

What is meaningful Consent under Uganda’s Data Protection Law?

Consent is a key principle of Uganda’s Data Protection and Privacy Act, 2019. It gives a data subject the right to control the collection and processing of their personal data, subject to specifically defined exceptions such as national security, public interest and medical purposes among others. Specific provisions make it a criminal offence if any collection or processing is made without consent.

Section 7 of the Act expressly prohibits the collection or processing of personal data without the prior consent of the data subject. “Processing” under the Act includes the disclosure of information or transmission of collected data. It is arguable that the transfer of personal data to Airtel Mobile Commerce amounts to “processing” under Ugandan data protection law. Did Airtel and the related company receive prior and meaningful consent to process and to use their customers’ data? In order for consent to be considered meaningful under the Act, it should be freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous. Does the Airtel notice meet these requirements?

- The Element of Freedom to Consent

Was there a real choice for the customers to consent to the processing and use of their data by Airtel and the “related” company? It can be argued that the Airtel’s statement, “Continued use of the service shall be taken as your acceptance” is a ‘’take it or leave it’’ requirement with little room for customers to effectively exercise their privacy choices. It is our contention that consent given under the threat of not being able to use a desired service, does not meet the requirements of meaningful consent envisaged under the Act.

The communication from Airtel “coercively” informed customers that their continued usage of the mobile money service automatically translated to consenting to the transfer of their data to the related company.

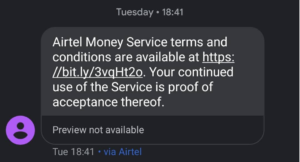

The Airtel mobile money users had not been given the chance to read the terms and conditions of service. In an attempt to cure this irregularity, Airtel sent out another message to users directing them to a link with the terms and conditions of service and still emphasized that, “Your continued use of the service is proof of acceptance thereof.” However, the Act requires that consent is given prior to the transfer. It can be argued that since the communication by Airtel was an afterthought, it possibly violated the requirement for prior consent.

- The Legal Relationship between Airtel and Airtel Commerce

Under the law, regardless of the similarity in shareholding of companies, each company remains a distinct corporate person. This is the hallmark of company law- that companies are separate legal persons. Airtel and Airtel Mobile Commerce are two distinct companies, consequently making Airtel Mobile Commerce a third party to Airtel’s customers.

Users of Airtel money have a contractual arrangement where Airtel is permitted to access, use and process personal data of its users, which includes mobile money data. That contractual arrangement cannot be used as a basis to transfer data to the sister company or a third party without the prior consent of the users/customers.

- Knowledge as an element of consent

Consent under the Act is based on an obligation to inform the data subject in a clear and transparent manner before the collection or processing of their data. In its form, the communication does not bear an explanation to the customers of how their information will be used by the sister company. It can be argued that given the disparity in knowledge and power between Airtel and its customers, Airtel customers are in fact unable to exercise meaningful choices with regard to the transfer of their personal information.

Even though Airtel has taken the liberty to notify its users about the implications of the continued use of their services, this notice falls short of the requirements of consent.

If Consent is Problematic

The communication made by Airtel requires us to examine whether a “consent model” of data protection is still the most efficient way of securing privacy rights. David Medine, a leading Privacy Consultant, states that consent (informed consent) is premised on knowing how your data will be used and agreeing to those uses. In this instance, could Airtel customers have envisaged that Airtel would set up another company to process their mobile money business? This is highly unlikely.

Scholars and practitioners, argue that there is a growing recognition around the world that consent no longer works as a mechanism to protect personal data. And perhaps, the coercive element of telecommunication companies, information technology companies and websites which frame consent as a “take it or leave it” without giving options to users to opt out, makes that point clearly. Professor Daniel J. Solove of the George Washington University School of Law, contends that many privacy harms are the result of an aggregation of pieces of data over a period of time by different entities. He comments that, it is virtually impossible for people to weigh the costs and benefits of revealing information or permitting its use or transfer without an understanding of the potential downstream uses, further limiting the effectiveness of the privacy self-management framework.

Further, Gayatri Murthy, cites India as an ideal example, where the draft data protection law breaks the reliance on individual consent as the means to protect data and puts the obligation on providers to act in its customers’ best interests. Professor Solove’s assertions further augment this view and he states “Until privacy law recognizes the true depth of the difficulties of privacy self-management and confronts the consent dilemma, privacy law will not be able to progress much further”.

However, disregarding the consent model takes away the individual’s autonomy to decide their rights and leaves them at the mercy of data collectors. Another challenge with David Medine’s propositions are that it would still be difficult to ascertain what may be regarded as the best interest of the data subject. This can be highly subjective and could be interpreted by data collectors to favor their commercial interests. At least with consent, one can make a reasonable inference that the decision was made by the data subject themselves.

Conclusion

Regardless, “coercive consent” and the ability of companies to retain massive quantities of data, require us to rethink consent as a model of privacy protection. Such communications by large corporations must be examined for their compliance with data protection laws. Our society might benefit from litigation and the exercise of authority by the Data Protection Office specifically regarding the requirements of consent in relation to the collection and processing of personal data. Without that, Twitter shall remain the arbiter for data protection in Uganda.

Written by

Joel Osekeny, Paul Epodoi and Joel Basoga.